From Theory to Practice

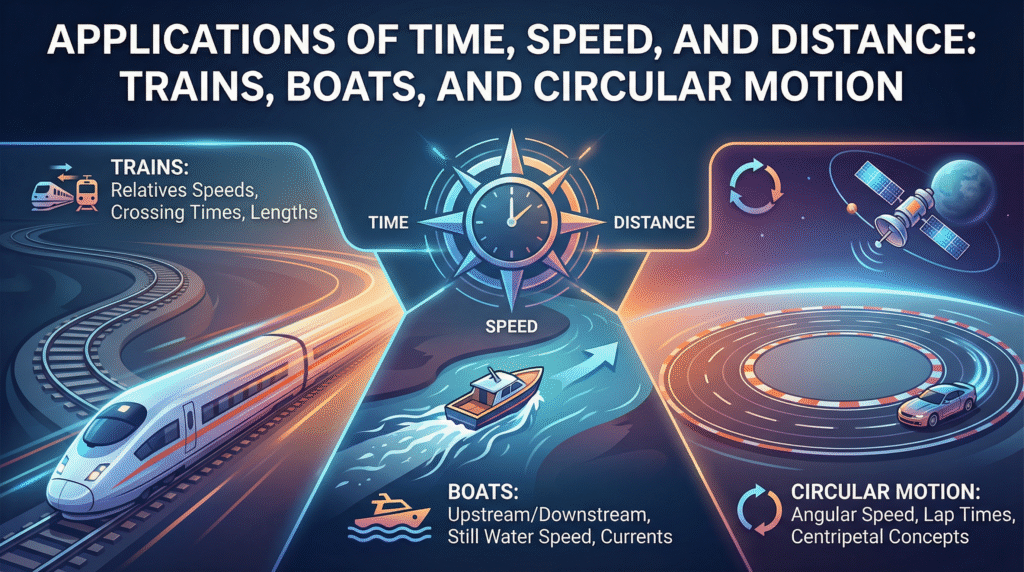

The fundamental principle of Time, Speed, and Distance (Speed × Time = Distance) extends far beyond abstract problems. In this exploration, we examine how this core relationship manifests in three practical domains: train movement, boats navigating streams, and circular motion. Understanding these applications requires grasping how the basic formula adapts to more complex scenarios with multiple variables and relative motion.

Problems on Trains: Accounting for Length and Relative Motion

Train problems introduce two critical modifications to basic TSD calculations:

Key Concept 1: Relative Speed

When a train crosses a moving object, you must use the relative speed between the train and that object, not just the train’s absolute speed.

Key Concept 2: Distance Includes Length

When a train crosses an object with measurable length, the total distance the train must travel equals its own length plus the length of the object being crossed.

Understanding Train Crossing:

Imagine standing on a platform as a train passes. The crossing process begins when the engine aligns with you and completes when the last compartment passes by. For the train to “completely cross” you, it must traverse its entire length—your standing position is essentially a point with no length.

The Four Essential Cases:

Case I: Train Crossing a Stationary Point

A train of length l meters passing a stationary object with no length (like a person on a platform) requires time equal to covering l meters.

Formula: Time = l / Speed

Case II: Train Crossing a Stationary Object with Length

A train of length l meters crossing a stationary object of length m meters (like another train, a platform, or a bridge) requires time equal to covering (l + m) meters.

Formula: Time = (l + m) / Speed

Case III: Two Trains in Motion—Relative Speed Calculation

Subcase IIIa: When trains move in the same direction at speeds u m/s and v m/s (where u > v):

- Relative speed = (u – v) m/s

- The faster train approaches the slower train at this reduced rate

Subcase IIIb: When trains move in opposite directions at speeds u m/s and v m/s:

- Relative speed = (u + v) m/s

- The trains approach each other at the combined rate

Case IV: Two Trains Crossing Each Other

Subcase IVa: Two trains of lengths a and b meters moving in opposite directions at u m/s and v m/s:

- Total distance to be covered = (a + b) meters

- Time to cross each other = (a + b) / (u + v) seconds

Subcase IVb: Two trains of lengths a and b meters moving in the same direction at u m/s and v m/s (where u > v):

- Total distance = (a + b) meters

- Time for faster train to cross slower train = (a + b) / (u – v) seconds

Practical Principle: Once you internalize these cases and practice applying them, train problems become systematic rather than complex. The framework provides a clear path through what initially appears complicated.

Boats and Streams: Managing External Force Variables

Boat problems introduce environmental variables absent in train scenarios. Two key factors determine a boat’s speed:

- Boat’s inherent speed (speed in still water) = u km/hr

- Stream’s speed = v km/hr

Directional Terminology:

- Downstream: Movement in the direction of stream flow

- Upstream: Movement against stream flow

The stream either aids or opposes the boat’s motion, requiring adjusted speed calculations.

Two Essential Cases:

Case I: Given Boat Speed and Stream Speed

When you know the boat’s speed in still water (u km/hr) and stream speed (v km/hr):

- Speed downstream = (u + v) km/hr (stream aids movement)

- Speed upstream = (u – v) km/hr (stream opposes movement)

Case II: Given Downstream and Upstream Speeds

When you know the speeds in each direction but need to extract component values:

- Speed in still water = [(a + b) / 2] km/hr (average of both speeds)

- Rate of stream = [(a – b) / 2] km/hr (difference between speeds divided by 2)

Key Insight: The upstream and downstream speeds are symmetric around the boat’s still-water speed. The still-water speed is the midpoint; the stream creates equal and opposite adjustments in each direction.

Circular Motion: Relative Speed on Closed Paths

Circular motion presents a third variation where bodies move around a closed path. The fundamental principle remains speed-based, but the geometry changes the interpretation of “passing” or “meeting.”

Two Movement Scenarios:

Same Direction Movement:

When two bodies move around a circle in the same direction with speeds a and b (where a > b):

- Relative speed = (a – b)

- The faster body gradually increases its distance from the slower body

- Eventually, the faster body completes an extra lap and aligns with (overtakes) the slower body

- This alignment is called “overlapping”

Opposite Direction Movement:

When two bodies move around a circle in opposite directions with speeds a and b:

- Relative speed = (a + b)

- The bodies approach each other at the combined rate

- They meet more frequently than in same-direction scenarios

The Overlapping Concept:

In circular motion, “overtaking” has a distinct meaning. The faster body doesn’t simply pass the slower body once—it continuously increases its angular distance until it has traveled one complete lap more than the slower body. This moment of alignment is when the faster body has “lapped” the slower one.

Unified Framework: Adaptation and Consistency

These three applications—trains, boats, and circular motion—demonstrate how a core principle adapts to different contexts:

| Context | Variables | Relative Speed Rules | Distance Consideration |

| Trains | Lengths of both objects | Same/opposite direction rules apply | Sum of lengths when crossing |

| Boats | Stream speed, direction | External force adds or subtracts | Direct distance × time relationship |

| Circular | Circumference, paths | Same/opposite direction rules apply | Lap completion and alignment |

Problem-Solving Methodology

Approaching these applications effectively requires:

- Identify the context: Train, boat, or circular motion?

- Extract given information: Speeds, lengths, directions

- Select the appropriate case: Which formula matches your scenario?

- Apply relative speed rules: Same or opposite direction?

- Calculate systematically: Use the formula for your case

- Verify reasonableness: Does the answer make intuitive sense?

Why These Concepts Matter

Understanding TSD applications goes beyond problem-solving mechanics. These principles appear in real-world scenarios:

- Transportation planning: Scheduling trains and calculating crossing times

- Logistics: Managing boat and barge movements through waterways

- Circular track sports: Understanding relative performance in cycling, running, or racing

- Manufacturing: Tracking relative motion of components on assembly lines

Building Mastery Through Practice

Like any technical framework, mastery develops through deliberate practice. As you work through examples:

- Start with simple cases (stationary objects, single variable)

- Progress to complex scenarios (multiple moving objects, multiple variables)

- Build speed and accuracy through repetition

- Develop intuition about which approach applies to which situation

The apparent complexity of these problems diminishes significantly with practice. What initially seems tricky becomes routine once you internalize the case structures and relative speed principles.

Conclusion: Pattern Recognition and Systematic Application

Applications of Time, Speed, and Distance demonstrate how mathematical principles scale across different domains. The same fundamental relationship (Speed × Time = Distance) and the same relative speed rules apply whether you’re analyzing train crossings, boat movements, or circular motion.

The key to mastering these applications is recognizing that they’re not genuinely different problems—they’re variations on the same theme, each with specific case structures that make them tractable. By understanding these case structures and practicing their application, you develop the ability to approach similar complex problems with clarity and confidence.